In today’s environmental crisis, choosing the right biodegradable packaging has become crucial for businesses and consumers alike. With conflicting claims about degradability, understanding the difference between truly biodegradable packaging and pseudo-degradable alternatives is essential for making informed decisions that genuinely benefit our planet.

I. The Packaging Dilemma

Globally, approximately 350 million tons of plastic waste are generated annually, with 60% of “degradable” packaging becoming microplastic pollution due to technical limitations.

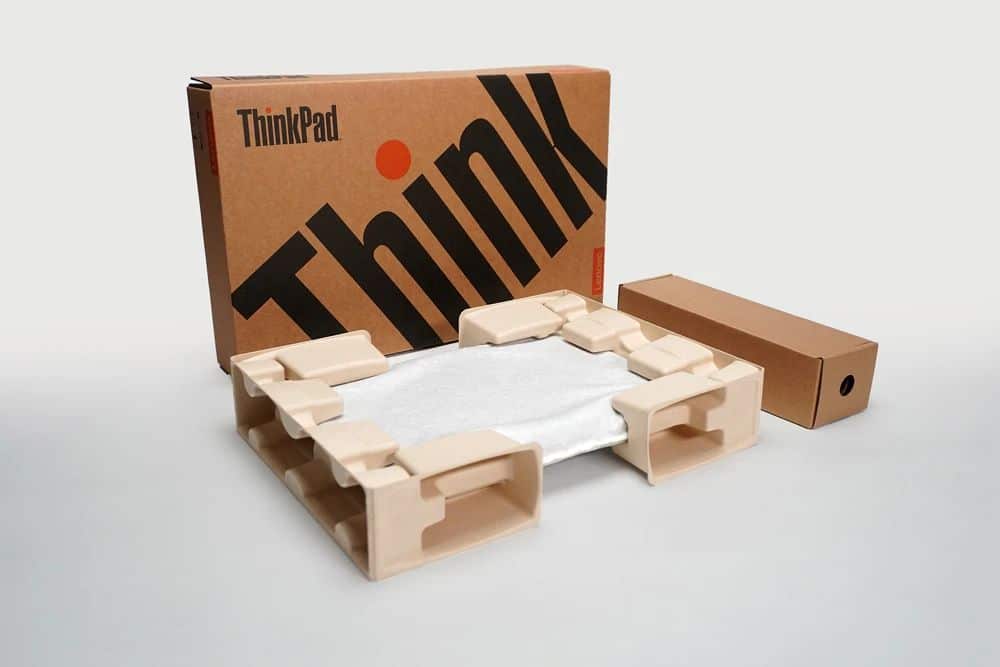

Against this backdrop,FSC-certified wood/bamboo pulp fully biodegradable packaging stands in stark contrast to industrial compost-dependent materials like PLA and starch-based plastics. This technological competition essentially pits natural cycles against industrial dependency.

II. Material Comparison: Natural Biodegradation vs. Industrial Compost Dependency

FSC Wood/Bamboo Pulp Fully Biodegradable Packaging

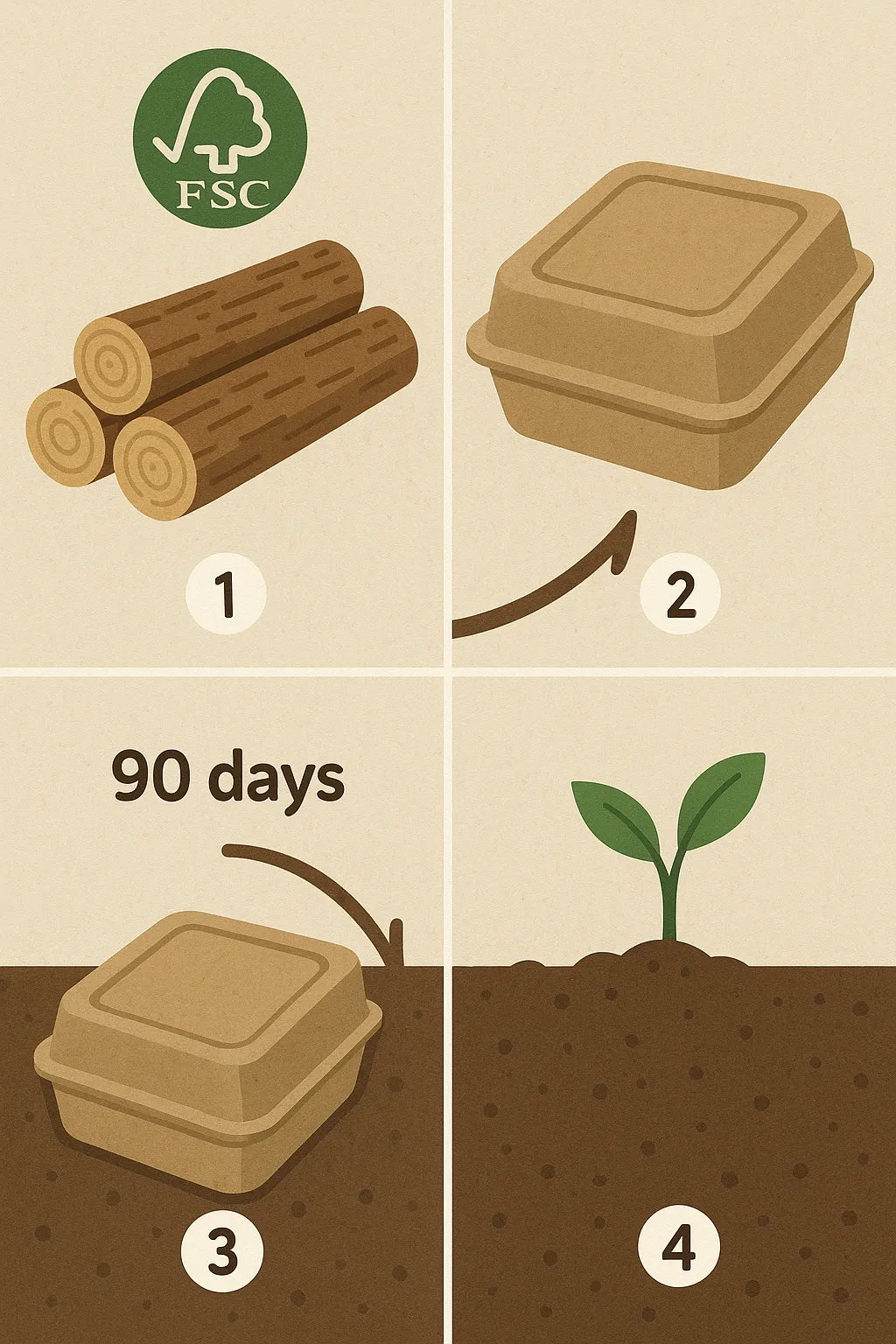

Raw Materials: Uses FSC certified bamboo & wood pulp, ensuring materials come from sustainably managed forests with strict ecological protection standards.

Degradation Mechanism: Biodegrades through microorganisms in natural environments, transforming into water, carbon dioxide, and organic matter within 3-6 months, without requiring industrial composting conditions.

Certifications: Complies with China’s GB/T 38082–2019 full biodegradation standard and meets the EU Green Claims Directive’s plastic-free requirements.

Pseudo-Degradable Products (PLA, Starch-Based Plastics)

Raw Materials: PLA is synthesized from fermented corn starch but relies on fossil fuel extraction processes; starch-based plastics typically contain petroleum-based components like PBAT/PBS.

Degradation Mechanism: Requires industrial composting environments above 60°C; cannot decompose in natural conditions and often fragments into microplastics.

Standard Deficiencies: The EU now restricts PLA similarly to conventional plastics due to its behavior in natural environments being virtually identical to regular plastic.

Comparative Data

| Indicator |

FSC Fully Biodegradable Packaging |

PLA/Starch-Based Plastics |

| Natural Degradation Period |

3-6 months |

Non-degradable (microplastic residue) |

Carbon Emissions

(tons/ton of product) |

0.8-1.2 |

2.5-3.0 (including hidden carbon costs) |

| Recycling System Dependency |

None, natural cycle |

High dependency (actual recycling rate<10%) |

| Microplastic Pollution Risk |

Zero |

High (soil/water contamination) |

III. Four Disguises of Pseudo-Degradable Products and How to Identify Them

1. Industrial Compost Dependency Disguise

- Example: PLA bubble wrap labeled as “fully biodegradable” but requires specific high-temperature composting conditions; behaves like regular plastic in home composting.

- Identification: Check if packaging is marked “for industrial composting only”; if not, it may involve false advertising.

2. Mixed Component Deception

- Example: Starch-PP food containers with 30% starch + 70% polypropylene, leaving microplastic residue after degradation.

- Identification: Burn test–pseudo-degradable starch-based materials produce black smoke and hard residue when burned; FSC fully biodegradable paper bags leave no residue.

3. Ambiguous Certification Labels

- Example: PE + bamboo powder packaging self-described as “eco-friendly” but lacking FSC or other environmental certifications.

- Identification: Look for FSC CoC (Chain of Custody) certification, which supports raw material traceability.

4. Low-Cost Price Trap

- Data: Pseudo-degradable plastic bags cost approximately $0.03 each, while FSC fully biodegradable paper bags cost 3-4 times; the lower price transfers environmental costs elsewhere.

IV. Conclusion: Returning to Nature as the Ultimate Solution

Truly sustainable packaging should not transfer degradation responsibility to industrial systems. Instead, like FSC wood/bamboo pulp materials, it should complete its lifecycle within natural cycles.

A green economy future can only move from slogan to reality when businesses choose 100% naturally biodegradable technologies, consumers vote with scientific awareness, and policies provide rigorous standards.